Common Traits of Some of the World’s Great Doers

I finished reading FROM SILK TO SILICON: The Story of Globalization Through Ten Extraordinary Lives by Jeffrey E. Garten and enjoyed it.

He tells (as you might surmise) the story of how we became a globalized society through the lives and accomplishments of ten people throughout history (up until the year 2000). The book was written in 2016, with a new preface added in 2017.

He starts with Genghis Khan and goes up to Deng Xiaoping (the Chinese dictator who opened up China for world trade), with lots of interesting people in between.

What I like about the book is it’s essentially 10 mini biographies weaved together, and it gives you the long view of the evolution of our interconnected world.

It gave strong Spaceship Earth at EPCOT Center vibes.

Note: You can also listen to this article here.

Who’s Who

I won’t get into gritty details of everyone (you can read the book if you’d like to do that), but there are a couple of overarching themes with each person:

They were doers, not just thinkers. They actually performed some act (like building the Silk Road, creating the transatlantic cable, privatizing government businesses).

They were also deeply flawed (greedy, murderers, slave traders)

The book also quotes Lord Acton, who said, “Great men are almost always bad men.” This is from his same letter that brought us, “Power corrupts; absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

All of these people were highly focused on achieving a single goal, essentially at all costs.

But we are all flawed, and as Ryan Holiday says in his book Courage is Calling, “let us look at the courageous moments…rather than focusing on another’s flaws as a way of excusing our own.”

The people were:

Genghis Khan

Prince Henry the Navigator

Robert Clive

Mayer Amschel Rothschild

Cyrus Field

John D. Rockefeller

Jean Monnet

Margaret Thatcher

Andrew Grove

Deng Xiaoping

Aside from the overarching themes the author highlights, I noticed a few common threads with most, if not all, of the people listed in the book.

They Understood the Importance of Effective Communication

The first thing that struck me was the high priority these people put on clear, fast communication.

Genghis Khan set up a postal system (called “Yam”) along the Silk Road and made sure it was safe for people to pass messages along.

Prince Henry shared what he learned with other explorers so they could use their shared knowledge to push further than ever before.

Mayer Amschel Rothschild set up offices around the world, and had his brothers and sons send letters in specific color envelopes noting good or bad news with the markets. This allowed his courier to go to the post office a few days before the mail was actually delivered and get the news earlier.

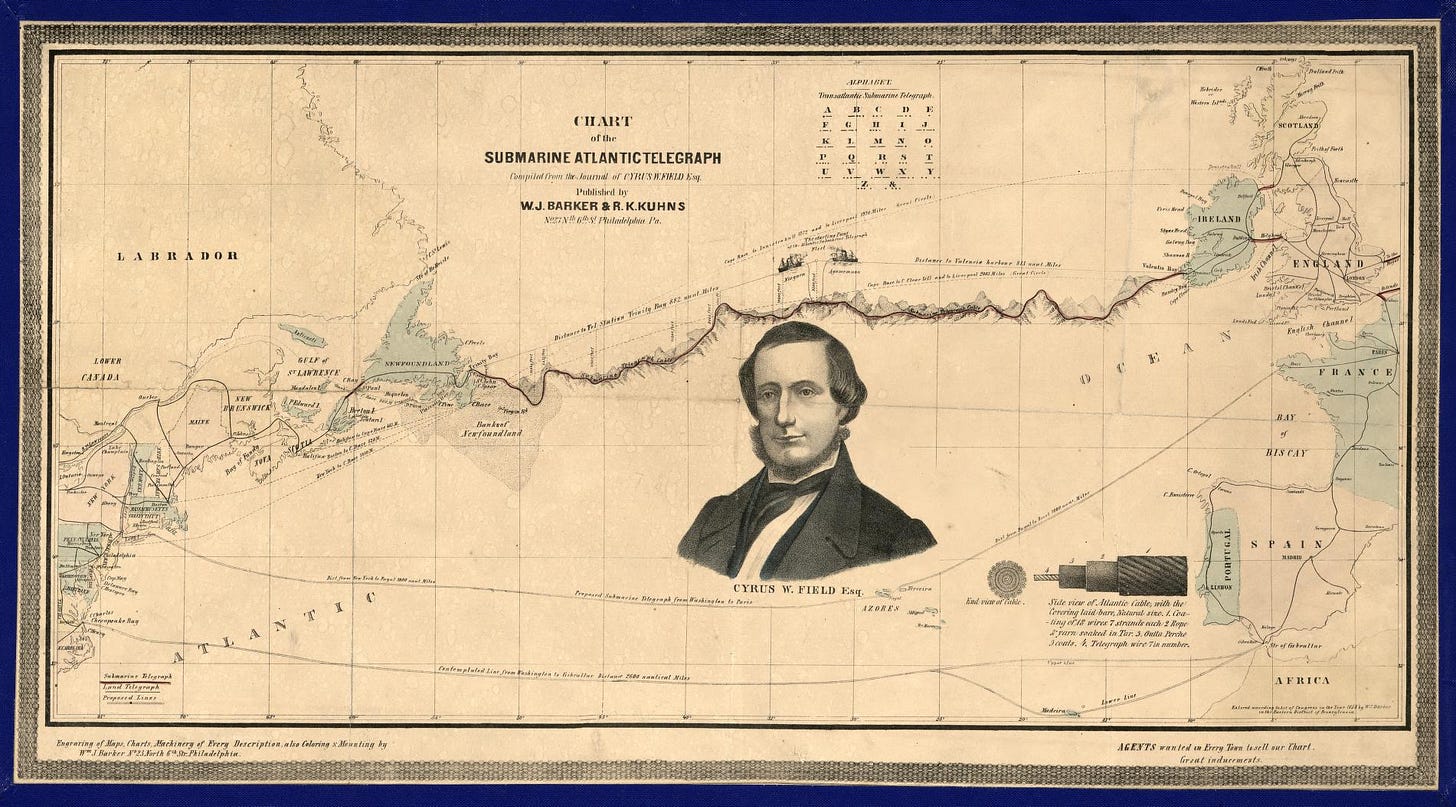

Cyrus Field dedicated a lot of his life to building the first transatlantic, underwater telegraph cable so that news could travel from the United States to Europe in minutes, not weeks or months.

Rockefeller had near perfect processes in place because he was communicating standards across continents. Making that as clear as possible was important to keep everything running smoothly.

Jean Monnet and Margaret Thatcher understood that in order for their ideas to catch, they needed to distill those ideas into something simple to understand and clearly communicate.

Without effective communication, they could not have built their empires, their companies, their global advancements. They wouldn’t have been able to reimagine and evolve long-entrenched ideas.

Communication was at the heart of what each of these people did, and it enabled them to take world-changing action.

You Can’t Go It Alone

Another strong trait in each of these people was understanding the need to cultivate good relationships.

Without good people to work with, you cannot accomplish much. These leaders knew that, and made sure to build good relationships.

Genghis Khan’s empire was reminiscent of what the United States did hundreds of years later. He had a small set of rules, but knowing he was uniting many independent tribes, he encouraged freedom of religion and culture. He appointed people whom he trusted and then rewarded them handsomely for their loyalty.

Deng Xiaoping, seeing the very opposite under Mao Zedong, encouraged the people under him to work and experiment freely (under some guidance) in the realms of economics and science. Whereas Chairman Mao ruled with an iron fist and fear, Deng ruled more openly in some areas during his rule.

Rothschild and Monnet knew the importance of building relationships with powerful people, then diligently serving those people behind the scenes. Monnet astutely observed that politicians wanted credit for big ideas, but didn’t necessarily want to do the work, so he put leaders’ names on his plans to encourage adoption.

Cyrus Field built a ton of relationships in his paper business and travels, which he then leveraged when it was time to fund his transatlantic cable project. Those relationships gave him the runway of over a decade’s worth of work, and several failures before he finally got it working.

On top of being a clear communicator, Margaret Thatcher’s ascent to becoming the first female UK Prime Minister and one of the most influential world leaders in the post-WWII era could not have happened without good relationships.

As a result, most of these people were also excellent at delegating. They knew they had limited time, skill, and resources. So they recruited people to help them. The strong relationships they built allowed them to do that, and know their important work was being done as well as possible.

They Were Focused

Garten makes this point at the end of his book: each of these people were doggedly focused on their mission. Rockefeller wanted to control the entire supply chain and spent decades building it. He lived in a tumultuous economic time and wanted to protect against losing everything.

Field’s sole focus was on getting the transatlantic cable working and spent years of his life making it happen, failing many times along the way. He knew that reducing the time it took to send a message across the Atlantic to near instant would change the world.

Andy Grove put Intel on the map by focusing fully on building smaller microprocessors — even letting go of other parts of Intel’s business because he knew he wanted to dominate this one niche (which he did).

Thatcher wanted to reduce the reliance on government as much as possible, privatizing much of what was government-run in post-WWII Great Britain.

Monnet wanted a more unified Europe, and dedicated nearly his entire life to it — a dedication that continues to pay off decades after his death.

Robert Clive was focused on expanding the British Empire and the British East India Company, pioneering methods for global commerce along the way.

Some would argue that these folks were too focused. Hearkening back to Lord Acton’s quote about great men, they were focused on their goals at all costs.

Grove was a harsh and paranoid manager. Monnet worked his team to the bone. Thatcher’s approach was considered cold and callous to the less privileged. Clive, Khan, and Prince Henry all did objectively evil things.

That doesn’t void the fact that focusing your time and energy on achieving a goal you truly believe in makes you highly motivated. Many of these people had everything to lose if they failed. Some did end up losing a lot. But their lasting legacy shaped the world.

They Actually Did

And that brings me to the last point — another one that Garten specifically called out. They were all doers.

They didn’t just think about stuff. They actually put their plans into action. It’s easy to sit online and think about what you should do. And it’s even easier to make excuses.

It’s a lot easier for critics to reach us these days. But what I try to remind my clients, my kids, and myself, is that it’s easier to complain than it is to create.

My friend Chris Lema says, “hope is not a strategy,” but too many people “hope” for stuff to happen. They “manifest” and “pray” they’ll get what they want.

These people actually did. They had big dreams, and they achieved those dreams.

I’m under no delusion that what I do will change the world like these folks. What some of these people did came at great cost. I’ve said several nice things about Genghis Khan, but we should not forget he was a vicious murderer...more so than most in a time basically defined by brutality.

I don’t condone everything these people did, but it’s undeniable that they changed the world for the better in many ways. I also try to remember that we don’t know how we would act during those time periods.

Instead, let’s separate the mechanics from the methods. By biasing towards action, we’re doing a lot more than just wishing things would change.

Take the good lessons and do something great: communicate well, build good relationships, and take focused action on something you truly believe in.